Urban Drilling – Opportunities Rising, Cities Sinking

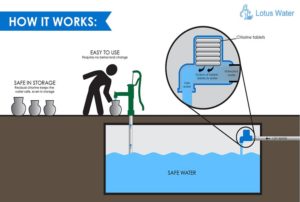

Around the world, cities in low and middle income countries are growing rapidly. With this rapid urbanization, often already weak water supply infrastructure cannot cope or keep up. Many cities are in low-lying areas on shallow aquifers. So why wait for a pipeline to be built, when you can just dig down to find water?

Manual drilling is tough work, but start-up costs for equipment are low. A team of drillers can work in a confined space, an alley or backyard, where a mechanized rig could never reach. There is also a market for conventional motorized drilling because in many cities hotels, factories and offices cannot operate if the water quality and quantity is not consistent or if water is rationed. For households, getting a connection is either a pipe dream or not a priority. This is particularly true in slum and peri-urban areas where alternatives are either free (springs, or shallow wells) or convenient (bottled or sachet water).

Drawbacks

At first glance, a private water supply, such as a borehole in the backyard, is a very sensible, rational response; water users are taking back control over an essential daily resource. Using low cost technologies, such as manually drilled wells and simple pumps should also be pro-poor. In many rural areas this is certainly the case; however in cities and towns, it is generally richer households, and businesses, that can afford to drill deeper wells with better well-head protection. They drill wells to adapt to the poor city water service, but also to avoid paying their water charges. This just deprives the utility of revenue that could improve service and cross-subsidize across the network to serve poorer areas.

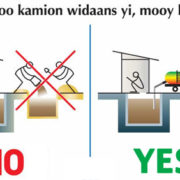

Poorer residents only have shallow wells. Shallow wells are the first to dry up, be contaminated by nearby pit latrines and uncontrolled industrial discharges, or in coastal areas become brackish and then unusably saline. The poor must then travel further each day to collect water, or to buy over-priced and unsafe water from water vendors who bring water in by trucks. They could drill deeper, but with declining water levels from so many private abstractions in small area, it is a race to the bottom.

Though the rich are not immune. In Jakarta, Indonesia, much of the city is sinking at the rate of 3-10cm per year because of groundwater pumping from private boreholes. Buildings and infrastructure are cracking and portions of the city are dropping below sea-level, an issue during the monsoon season1.

Looking Forward

A research project, called T-GroUP, is working in Arusha (Tanzania), Dodwa (Ghana) and Kampala (Uganda) to understand how groundwater is used in slum areas. Thier innovative method called ‘Transition Management’ manages the social, technical, political and economic feedback loops to achieve better groundwater management, that benefits everyone.

In the meantime, it is clear that if the common good cannot be achieved through unfettered market forces, then government needs to step in and regulate effectively and fairly. For such successful regulation, they need openness and transparency to eliminate the space for corrupt practices. City water utilities also need to be able to provide a high quality, affordable, and accessible service. In rapidly growing cities, utilities could consider a modular approach to water supply that brings in groundwater recharge and rainwater harvesting. Good customer service is essential; smart, easy payment systems are increasing revenue collection. For example, in Kampala, Uganda you can pay your water bill easily by phone app, SMS or phone call. In general, people pay for convenience, so the route to success is to make water supply as easy as turning on a tap.

Further reading:

- Urban Groundwater Dependency in Tropical Africa (2017)

- UPGro: T-GroUP: Experimenting with practical transition groundwater management strategies for the urban poor in sub-Saharan Africa

1 Abidin, H. Z., Andreas, H., Gumilar, I., & Brinkman, J. J. (2015) Study on the risk and impacts of land subsidence in Jakarta, Proc. IAHS, 372, 115–120, 2015, proc-iahs.net/372/115/2015/, doi:10.5194/piahs-372-115-2015